Do cheaters in the lab cheat in the field as well?

One of the biggest criticisms that psychologists and behavior economists face is about external validity. External validity is a term used to describe the generalizability of experimental results conducted in the lab, to the real world setting.

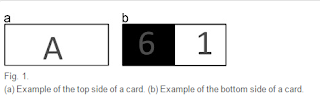

They conduct a variant of the Mind game as in Jiang (2013). There are twenty cards with the top part of the card labeled from A to T and the bottom part of the card has a black and white portion. The sum of the numbers in the two portions sum to 7. In the treatment "turn first", students choose a color in their mind, turn the card and write the earning of the chosen color, while in the "write first" treatment, students first write the chosen color and then turn over the card. In this experiment, the experimenter cannot directly observe the choice of participants. The reason they had two treatment groups is that the "turn first" treatment measures implicit cheating and the "write first" treatment measures explicit cheating. In the "turn first" treatment, a participant can cheat by reporting the higher payoff regardless of his initial choice, while in the "write first" treatment a participant can cheat by overwriting his previously mentioned choice, or by turning the card before he writes his choice. The figure below describes how a card looks like.

|

| Source: Potters & Stoop (2016) |

Participants were handed out a card mentioning their earnings and the email ID of the experimenter. They were told that the card would help them get in touch with the experimenter in case they had questions about payment of the experiment.

Some participants were "overpaid" 5 euros, some participants were "underpaid" 5 euros while the rest received a "normal pay". An email was sent to the participants three days after the payment with the following text "We would like to inform you that we have transferred your earnings from the experiment to your bank account (… euros). Could you please verify that you have received your earnings? ". After 3 weeks, people who were underpaid were paid the remaining money.

Cheating on this experiment can be of two types. Cheating by omission involves not replying to the email, while cheating by commission involves replying to the email but not mentioning the overpay. A person is classified as a cheater if he cheated in either of the two ways. Amongst those who were underpaid, 75% of them replied to the email mentioning that they were underpaid. It is possible to assume that 75% of the people who were overpaid would also reply to the email. However, subjects in the overpay condition reply less often to e-mails and report less often, as compared to treatments ‘Normalpay’ and ‘Underpay’. A further statistical analysis reveals that those who cheat in the lab (top 25% performer), are less likely to reply to the email or to report their overpayment.

This paper is a great contribution to the field and would help researchers studying cheating behavior. I reckon, however, that this paper is despised by cheaters.

References:

Potters, J., & Stoop, J. (2016). Do cheaters in the lab also cheat in the field?. European Economic Review, 87, 26-33.Jiang, T. (2013). Cheating in mind games: The subtlety of rules matters. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 93, 328-336.

Rosenbaum, S. M., Billinger, S., & Stieglitz, N. (2014). Let’s be honest: A review of experimental evidence of honesty and truth-telling. Journal of Economic Psychology, 45, 181-196.

Comments

Post a Comment